Amalgamated Canvas: How Sri Lanka's Finest Architect Crafted His Self-Portrait Through Architecture

Geoffrey Bawa blended Sri Lanka spirit with European essence through the lens of vernacular architecture (Ordermade #8)

Every artist works on a different scale. A page. A painting. A sonata. A film. A novel. A house. A garden. But essentially they all create, in some ways, self-portraits of themselves. Art is a long intimacy. The scale of the achievement might be grand and take years but it has to be personal and carefully pieced together and specific to its culture

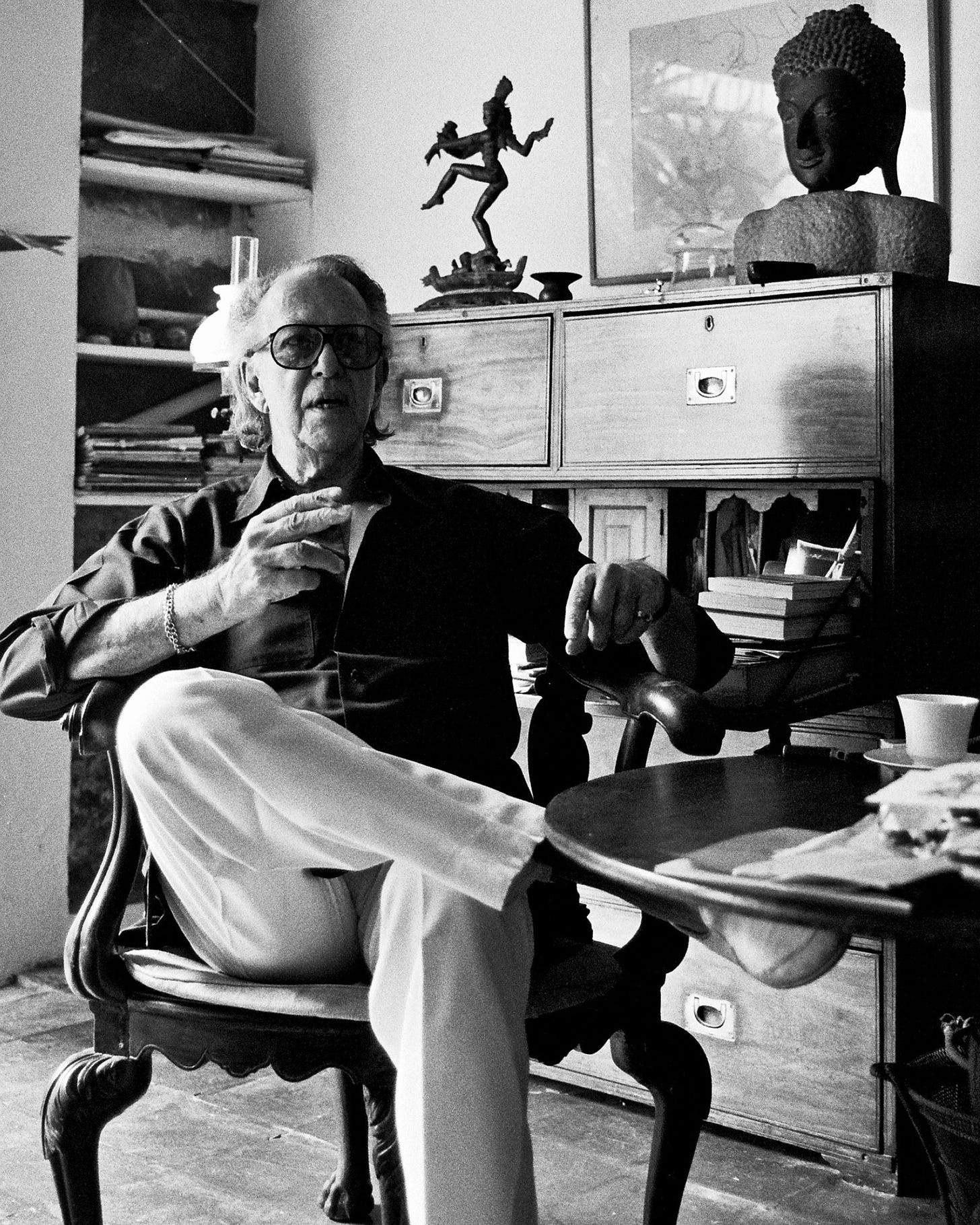

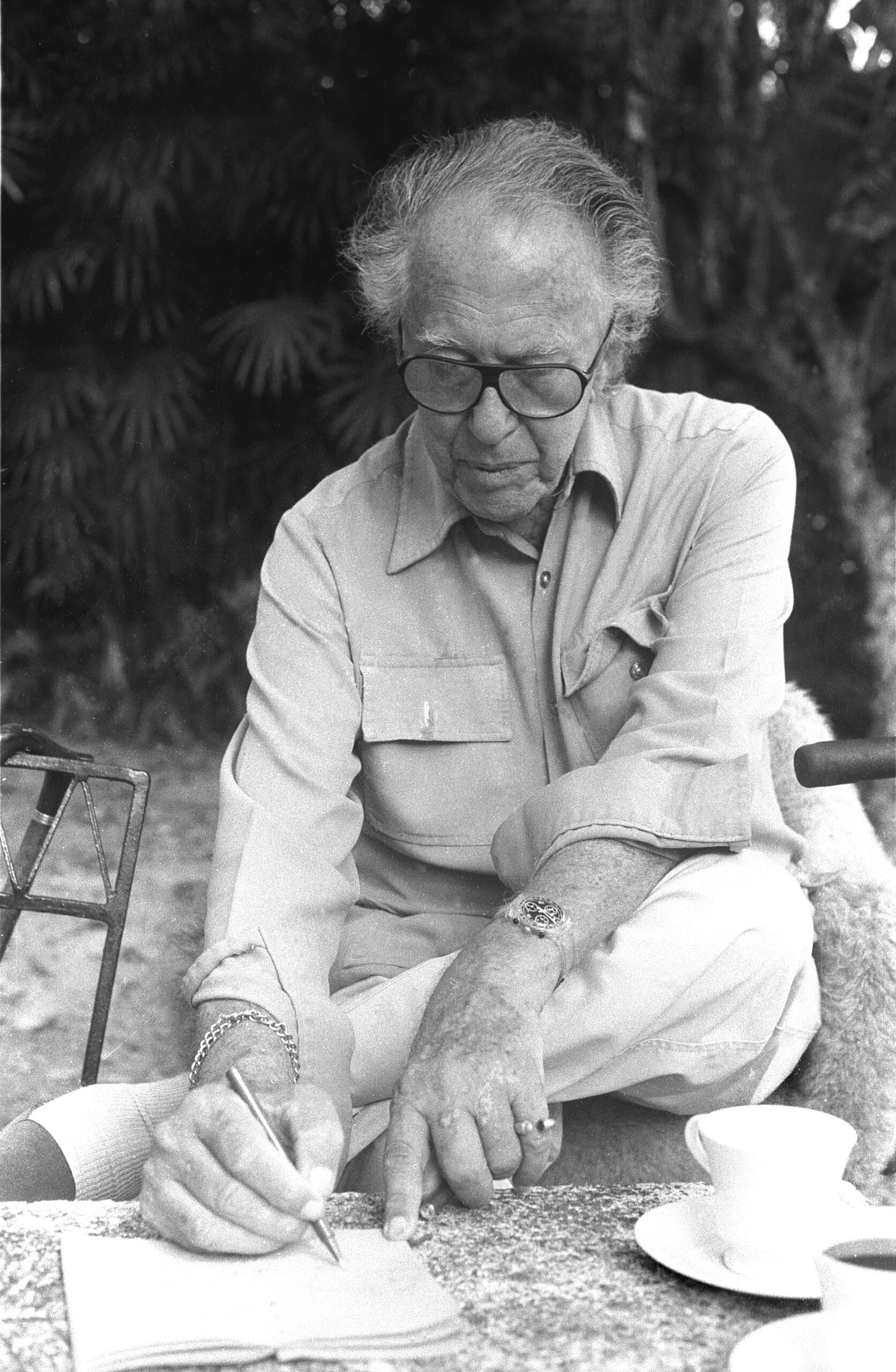

wrote Sri Lanka-born Canadian author Michael Ondaatje in a tribute to Deshamanya Geoffrey Manning Bawa.

Geoffrey Bawa's vernacular architecture—defined as a style rooted in local needs and traditions—resonates not only with the locale but also with his soul.

His architecture served as a canvas for self-exploration, reflecting his quest to reconcile his diverse cultural influences and find his place in the world.

There is a pleasant co-existence of seemingly disparate elements in his designs: a deep respect for the local environment, artisanship, a nostalgia for European summers, the luxury of an expensive European car, and a pragmatism rooted in Sri Lanka’s perennial austerity.

This nuanced amalgam shows up in the choice of materials, the design of the gardens and the courtyards, the utilization of empty spaces, and the art pieces he incorporated into his projects.

Esteemed as one of Sri Lanka’s leading architects, Bawa was known for his architectural style that melded his structures with the local Sri Lankan environment, showcasing his sensitivity to the natural and cultural context. His work embodies the multiculturalism emanating from his identity and diverse experiences.

Ordermade curates a weekly collection that captures the essence of こだわり or 'kodawari'—a deep dedication and care—in art, fashion, interiors, architecture, music, and literature with Japanese sensibilities.

Did someone forward this to you? Subscribe below.

Bawa’s Upbringing

Born in 1919 in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) during the last years of its status as a British colony, Geoffrey Bawa found himself at the crossroads of colonial legacy and an evolving national identity. His father, a wealthy individual of British and Sri Lankan Muslim heritage, practiced law. His mother was a Dutch Burgher of mixed Sinhalese, German, and Scottish descent.

Following his father's path, he initially aspired to be a lawyer. He studied English at Cambridge and had his legal education in London, where he was admitted to practice law in 1944.

His legal career started amid Sri Lanka’s nascent identity as an independent nation. However, the practice of law soon lost its appeal for him. So he embarked on a two-year grand tour, which included visits to Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia for soul-searching. He contemplated settling by Lake Garda in Italy, but his mother’s illness compelled his return to Colombo, his homeland.

Upon his return, he acquired Lunuganga, an abandoned rubber plantation, in 1948, the same year Ceylon gained independence from Britain and rebirthed as the Republic of Sri Lanka.

He harbored this vision to recreate the European summer he adored in Italy on his plantation. However, he realized his lack of architectural knowledge prevented him from realizing the vision.

This realization him to pursue the path of retraining as an architect. In 1954, his studies started at The Architectural Association School of Architecture, the oldest architectural school in the UK. He earned his architect’s credentials in 1957 at the age of 38.

I experienced an instant familiarity upon my first encounter with his architecture. Perhaps it was the semblance his works carry to the Japanese architecture I admire.

Turned out that Kengo Kuma, one of the biggest Japanese architects known for harmoniously combining Japanese traditions with modern architectural techniques, held Bawa in such high regard that he delivered the annual Geoffrey Bawa Memorial Lecture for his 100th birthday in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 2019. He said, “Bawa mixed western culture and Sri Lankan culture and his way of doing this was very different from the modernist culture that prevailed at the time... he changed the history of architecture in the 20th century and after him, we architects have gone in new directions.”

The subtle yet profound dialogue between built form and nature, the harmonious interplay of indoor and outdoor spaces, and the meticulous attention to simplicity and functionality—these attributes echoed the quintessence of Japanese architectural philosophy, fostering this sense of instant kinship.

Integration with Nature

The enormous Kandalama Hotel, designed in 1994, exemplifies Bawa’s architectural ethos of harmonizing built forms with nature.

This project, however, initially faced strong opposition from environmentalists and the local community, notably marked by a monk threatening self-immolation in protest against the project. But Bawa and the hotel management team turned the protestors into co-workers by taking various approaches to integrate the hotel into nature.

Bawa's environmentally-conscious design approach for the Kandalama Hotel is encapsulated in the following:

Among the unique environment protecting architectural steps taken by Bawa included the preserving of natural rock as well as a Nuga tree variety; and allowing rainwater to flow off the rocks and under the hotel, to the reservoir. The columns around the building and the rooftop were designed to support the growth of foliage from the surrounding environs and the state-of- the-art technology based waste recycling and aeration plant were mechanisms that made the village community and all critics realise that instead of ruining the environment, the hotel was contributing to safeguard it while providing much needed jobs to the village youth.

The hotel structure is seamlessly integrated into the jungle. It is constructed around a rock traversing the hotel from base to summit, evoking a sense of oneness with nature.

Further illustrating his nature-centric design philosophy, Bawa was known to capture the 'genius loci' in his works, integrating trees, boulders, watercourses, and views into the architectural fabric.

According to Mayer, who was Bawa's student and is now a successful architect, his designs were "as much amplifications of the natural places as they were the making of new places."

The gardens he crafted were no exception to his holistic approach to architecture. For instance, the garden of Lunuganga, as described by Krishna, one of Bawa's carers at the end of his life, is "a fascinating collage of Italian renaissance, Japanese botanical art, and English countryside layered on a mirage of Sri Lanka's ancient water gardens."

Blurring Indoor-Outdoor Boundaries

The seamless transitions between interior and exterior spaces are another hallmark of Bawa's architecture.

Consider the Ena de Silva House. Its design eradicates clear boundaries between indoors and outdoors, facilitating a fluid movement of people and air and a deeper connection with nature.

This architectural choice is not only aesthetically pleasing but also programmatic, as the unobstructed airflow through the living spaces provides natural cooling essential for the tropical climate.

The house evokes the essence of Engawa, a characteristic transitional zone or corridor typically encircling the perimeters of traditional Japanese homes. Whenever I find myself in a traditional Japanese home, one of my favorite things to do is just observe the beautiful transition of nature while seated on the Engawa.

Writer and researcher Lishani Ramanayake touches on the same point in her description of Lunuganga:

In what is perhaps its most ubiquitous characteristic, Lunuganga easily blurs the distinction between the interior of the domicile and the landscape around it: a delicately placed velvet tête-à-tête sits adjacent to a sun-mottled interior courtyard; massive wooden doors open into a sprawling garden overlooking the river; a double height loggia allows for a moment of stillness, surrounded by the low flutes of bird song.

Simplicity

Another standout feature in Bawa’s designs is the harmonious blend of simplicity and functionality.

He infuses life and soul into his projects through thoughtful choice of materials, art pieces, colors, and textures. Yet, all these elements come together nicely, ensuring the simplicity and the openness of the spaces remain unintrusive.

An exemplification of this philosophy is seen in the Sri Lanka Parliament Building, where the design, though simple, enhances interaction and showcases a harmonious blend of aesthetics and practicality. (Fun fact: the main constructor was a Japanese consortium of two Mitsui Group companies.)

Indigenous Natural Materials/Artisanship

Bawa also strongly advocated for utilizing locally sourced, natural materials and artworks to promote harmony with both the environment and local culture.

Bawa is often quoted as the pioneer of Tropical Modernism, but his version of modernism is not the typical modernism approach you'd see elsewhere; it’s both contextual and regional.

Bawa's first buildings classroom blocks for two Colombo schools and an industrial estate at Ekala - were essays in Tropical Modernism, incorporating simple white geometric designs, patterned brise soleils and supressed roofs.

However, it soon became clear to Bawa that, as well as being culturally inappropriate, Tropical Modernism could not cope with the humid heat of Ceylon: pure white surfaces discoloured, grilles let in rain spray, flat roofs leaked and over-heated. He began to experiment with the use of traditional elements such as verandas, courtyards, overhanging roofs, and locally produced materials such as clay tile, stone and timber, demonstrating that a contemporary architecture could still connect to the past and that, using traditional construction, it could still be spatially ambitious.

His regard for the local materials and culture stems as much from pragmatism as from aesthetical considerations. The following story, told again by Mayer, illustrates how traditional methods work better than internationalized modernism techniques:

I learned about amazing local craftsmen’s skills. While working on the hotel, Bawa disappeared for a few days. I was told he went to Burma to purchase teak trees, which then arrived in the next weeks on the construction site, cut into 4-inch-thick slabs. There were few power tools on the site, and I went back to the office and immediately proceeded to detail the hotel with my central European knowledge, and central European materials. Bawa laughed, and asked me to wait until we got back on site. When we did, we found amazing products which local teams had made out of the teak slabs, with hand tools. There were balustrades, windows, doors, and furniture, with wicker woven seats. “Your details would not last a season here in our climate,” he said to me. “We have traditional methods that will.” And so I stood in awe at technical assemblies that included plasters with animal hair reinforcements and connectors that used no metal, as the salty tropical air would make short shrift of them.

Bawa's approach was not about grandiosity, but about weaving a narrative that resonates with the soul of the land. His projects were dialogues between him and the genius loci, each element curated with a deep understanding of the historical and cultural resonance of the place.

Among the epitomes of this unique approach was the Bentota Beach Hotel, a project that showcased how a built environment could harmoniously coexist with, and even accentuate, the local artistic spirit. His collaboration with local artists was not merely a feature of the project, but its very essence, laying a foundation for a design narrative that was as local as it was modern.

In the Bentota Beach Hotel, a visitor ascends into the entry hall toward a large ceiling entirely made from local batik fabric. He carefully placed sculptures and ceramics throughout, hung large, bold paintings on the walls, and imprinted local leaves in custom-made tabletops. Bawa left little to circumstance—he carefully selected furniture and artwork, and often created parts of the interiors, too, from local materials... Materials were raw, but bold, light was ample, nature was always close, and interior space was generous. Art was ever-present throughout.

This philosophy also shines in The Lighthouse Hotel, where a unique iron staircase designed by Sri Lankan artist Laki Senanayake depicts a historical battle between native Sri Lankans and their Portuguese colonizers.

Bawa’s Dual Vernacular

More than anything, Bawa perhaps sought his architectural narrative to resonate not just with the locale it inhabited, but also with the vernacular of his own soul.

His Sri Lankan roots propelled him to deeply engage with the natural surroundings and the vibrant community of local artisans. Yet, the European streak within him, honed by his heritage and education abroad, wove a contrasting yet harmonious thread through his creations.

His works were a manifestation of this dual allegiance and maybe the only way to express this "in-betweenness" or the placelessness that comes with it.

The embodiment of this blended ethos finds a touching expression in the serene retreat of Lunuganga:

We sit on a bench that overlooks the Dedduwa Lake, flanked by two miniature statues of David purchased in Italy and assembled in Sri Lanka. I feel like I am looking out over a sun drenched Mediterranean villa; it is only the realities of the landscape—the frangipani trees, the sight of a Buddhist temple across the lake, a well shaped like a *bo* leaf—that bring me back to where I am. Lunuganga evokes a sense of overwhelming nostalgia—and for good reason. Before his mother’s illness brought him down to Sri Lanka, the British-educated Bawa had contemplated buying and settling down in a villa overlooking Lake Garda in Italy. It is this particular longing, this nod to the possibility of other homes on other shores, that Lunuganga so cleverly evokes.

The story woven through Geoffrey Bawa's career is more than a testament to his architectural mastery; it’s a deeply intimate exploration of self, a pathway that led him to the essence of his being.

His creations serve as a mirror, reflecting not only cultural amalgams but also a deep respect for nature. The careful interplay of local and foreign elements, the fluid dialogue between built form and nature, and the harmonious fusion of modernity with tradition, all evoke a narrative that is as deeply personal as it is universally resonant.

Through his works, Bawa didn't just create spaces; he embarked on a journey of self-discovery, exploring and eventually finding himself in attempting to express the inexpressible. I reckon, for some, art is the singular means to communicate their soul’s vernacular to the world—the only connection to the world when all else fails to help them find their place in it.

I’ll leave you with a beautiful reflection on Lunuganga by Ramanayake:

It is fitting that Bawa chose Lunuganga, the project that he spent his entire life working on, to be laid to rest. It also speaks to the fluidity of Lunuganga’s history, how it, much like the troubled country it called home, went through multiple incarnations and fulfilled a multiplicity of functions, from hosting devil dances to entertaining artists from around the world, transforming, over time, from an abandoned rubber estate to a carefully maintained private retreat that invites visitors to experience the great architect’s life and legacy in the way he would have wanted you to—with a slow, unhurried stroll through the landscape that he so loved, stopping, once in a while, for a coffee, a gin, a smoke, as the sun sets over the silvered waters of the Dedduwa Lake.

or

Sources: